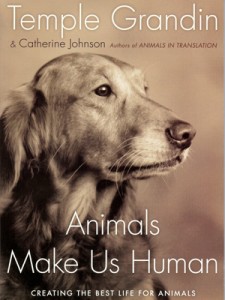

No time for a post yesterday–I was reading the last of Animals Make Us Human, by Temple Grandin before heading off to a workshop with her at the University of Washington. This was a very unique opportunity to sit down in a room with no more than a dozen people and engage in a lively conversation with Grandin and some students, faculty and staff at the UW. Temple Grandin has worked as a consultant to the animal slaughter industry for decades, redesigning slaughter plants so that they are better suited to making animals calm as they are going to their slaughter. As a person with high-functioning autism, Grandin claims to understand animals’ experience of the world more accurately than most because she ‘thinks in pictures’ the way animals might. This perspective has led her to observe that animals are spooked by certain small details which most humans would not notice, and removes these objects from slaughter plants. She has also redesigned the chutes for cattle to walk through at slaughter plants so that they will calmly proceed to the slaughter station without balking. As a young person, she designed a ‘hug machine’ as a method to calm herself down. She found that having pressure applied to her sides calmed any attacks she might have. Applying this same type of machine to animals in slaughter plants, she was able to design systems to pacify animals while they are being ‘stunned’ in the slaughterhouse. Grandin has set up audit systems for meat producing corporations to follow and has ultimately made a highly significant impact on the conditions of animals in the meat industry in the moments leading up to their slaughter.

For my Masters thesis, I looked at ‘humane slaughter’ in the United States meat industry and reviewed the federal legislation, the industry recommendations (written by Grandin), and the methods of alternative slaughter practices as well. Grandin’s recommendations are by far the most specific and rigorous of the guidelines out there with set limits for the percentage of animals allowed to be shocked with electric prods, or the number of animals allowed to vocalize throughout the process. Her guidelines can and have been voluntarily adopted by industry producers, but are not enforced by federal law. Laws governing animal welfare are shamefully lax. The Humane Methods of Livestock Slaughter Act (HMSA) is the only piece of legislation that protects farmed animals and it is impossibly vague. Additionally, it does not cover birds (chickens, turkeys, ducks, geese, etc), rodents (including rabbits), or fish (and other aquatic life). In the U.S. alone, at least 9 billion chickens are slaughtered each year for meat, and 300 million hens are caged in battery cages for egg production each year. This is just the number of chickens, not to mention all other ‘poultry’ type birds, rodents and fish. And these animals are all unprotected. As Grandin, and many animal advocates have written, chickens and other ‘poultry’ live the most horrific lives of any farmed animal. While Grandin does not associate this especially ill treatment with the lack of legislation for these particular animals, other experts in the field do make that connection.

Since beginning my project on ‘humane slaughter’ in 2009, I have had difficulty ascribing to Grandin’s view of animals in the food industry. Grandin will be the first to argue that animals have emotions and that they even have emotions similar to humans’, but nowhere in her arguments are these emotions cause for reflection on the use of animals for food. She is firmly a welfarist–concerned with making animals’ lives a little better while they’re being raised for food, but not concerned with questioning the structure that makes animals ‘food’ in the first place. For me, and many others before me (including Marc Bekoff, Jeffrey Masson, etc.), recognizing animals’ emotions logically leads to the realization that if given a choice, animals may not, in fact, want to be slaughtered for humans to eat. Nor should our interest in eating a burger or steak outweigh their interest in continuing to live their lives (Peter Singer made this argument when he talked about non-basic and basic interests). Grandin is probably the foremost advocate for ‘humane slaughter’ in the industry and she believes that the ultimate goal is for animals to have a ‘decent life and a good death’ in the meat industry.

This is not enough. Even if animals in the food industry are treated with the utmost kindness while they are alive and when they are slaughtered (which they are not), it is highly problematic to cut that life short at just a year or a year and a half. ‘Humane slaughter’ is an oxymoron. It’s a way to potentially make the death of animals in the food industry slightly less horrific. But fundamentally, humane slaughter is a way of desensitizing human consumers to the violence inherent in slaughtering any animal for food. Synonyms for ‘humane slaughter’ are ‘compassionate massacre,’ ‘merciful murder,’ and ‘kindly tear to pieces’. ‘Humane slaughter’ makes producers and consumers feel better about the meat they are producing and consuming and ultimately encourages the production and consumption of more meat.

Grandin has certainly made conditions in slaughterhouses less horrible for the plants that effectively adopt her methods. However, she is ultimately helping the industry to operate more efficiently, make more money, and slaughter more animals in less time. This is where I have difficulty getting behind her work. And yet, it is precisely her middle of the road, welfarist position that makes her appealing to the industry and has enabled their cooptation of her skills for their ends. It is precisely her clear dismissal of veganism as an option, her unwillingness to engage with those who advocate more radical approaches to thinking about the kinds of lives animals might want, and her dedication to making ‘more humane’ the status quo that has gained her access to the industry in this way. Her work is to be commended for its practical approach to making animals less frightened in those last moments before they are slaughtered. But it makes me shiver to think how many people think this is enough, how many people think this is an acceptable techno-fix for the very real problem of animal welfare in the food industry. Obviously, we need people like Grandin to be working on improving the current state of animals in the food system for the generations of animals who are suffering right now in an industry that is far from ‘humane’ (however we might define it). But, we also need people who are visionaries–like Gary Francione, like Gene Baur, like Jeffrey Masson and Marc Bekoff–who work for a very different kind of future for farmed animals–one where they are not farmed at all. A future where animals’ value is not based on their productive and reproductive capacities. This (what some may call radical) approach to thinking about animals is one that pushes people to think rather than pacifies them into complacency. It challenges our anthropocentric human exceptionalism, and it deconstructs false boundaries between ‘the human’ and ‘the animal’ that allow us to see animals in a whole new way.

Follow

Follow

Katie,

You make a clear and thoughtful rebuttal to the basic assumptions that support the concept of humane slaughter. I think it is interesting that Grandin claims to be able to understand animals better that most people because she thinks in pictures. What about the rest of the senses and the non verbals that all of us animals have and use to live in the world. Don’t you think animals use their senses (as well as their voices) to experience the world? How can they not experience terror when they smell and hear the pain of those who go before them into the slaughter house? Just asking.

I agree! Great point! I think it’s really important to consider the various sensory ways animals interact in the world–beyond just seeing. And I would imagine this is particularly relevant in a slaughterhouse, which is most often a noisy place with lots of strange smells, only one of which would be the blood of other animals. Thanks for posting these important questions!

Hi Katie,

I’m so glad I’ve found you! Can we connect over email? I’d like to put my mother in touch with you if you agree. She is moving back to Seattle to begin her retirement in June. She is currently a middle school teacher in Italy (american school) and is having her class work on issues around humane slaughter. Her students want humanely slaughtered meat ONLY in their schools! So she’s teaching them the art of activism.

That said, when she returns here she wants to continue this work. Based on what you’ve done, you seem like the perfect person to set my mom on the right path. She needs to be connected with the right action groups/people.

Are able to provide such info? If so please do email me at Bohedra@gmail.com

Thanks!

Bo Lee